Throughout the annals of history, humanity has borne witness to the remarkable rise and inevitable fall of countless technologies, each one telling its own unique story. Some of these innovations have become entirely obsolete, having been supplanted by solutions that are more efficient, reliable, or advanced in their capabilities. Conversely, there are others that have faded into obscurity, leaving behind only tantalizing remnants of their once-prominent existence, artifacts that spark curiosity and intrigue about the past. In this insightful blog, we will embark on a journey to explore some of the most fascinating lost technologies that are no longer utilized in our modern world. We will delve into their historical significance, assess the impact they had on society, and examine the multifaceted reasons behind their decline and disappearance from everyday life. Join us as we uncover these forgotten marvels of human ingenuity.

1. The Antikythera Mechanism

What It Is

Discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Antikythera, Greece, the Antikythera Mechanism is an ancient Greek analog computer dating back to around 150-100 BC. It was designed to predict astronomical positions and eclipses for calendrical and astrological purposes.

Why It’s Lost

Despite its remarkably advanced design, the intricate mechanism fell into obscurity after the gradual decline of the ancient Greek civilization, which marked a significant turning point in technological advancement. The comprehensive knowledge and understanding required to create such complex devices were unfortunately lost during the tumultuous period of the Middle Ages, when societal upheaval and cultural shifts led to a decline in scientific inquiry. It wasn’t until the 20th century, with the resurgence of interest in ancient technologies and a new wave of research and exploration, that scholars and researchers began to unravel and truly comprehend the complexity of these impressive devices, revealing the ingenuity of their creators and the sophistication of their engineering.

2. Roman Concrete

What It Is

Roman concrete, renowned for its exceptional durability and remarkable longevity, was utilized in the construction of numerous ancient structures, including iconic landmarks such as the Pantheon and the elaborate aqueducts that helped supply water to cities. Unlike modern concrete, which can experience deterioration and wear over time due to various environmental factors, Roman concrete has demonstrated an extraordinary ability to withstand the test of time, remaining intact for centuries. Its unique composition and ingenuity in application allowed ancient Roman engineers to create structures that not only served their practical purposes but also continue to inspire awe and admiration today.

Why It’s Lost

The exact recipe for Roman concrete, which included volcanic ash, lime, and seawater, was lost as the Roman Empire fell. Modern concrete lacks the same resilience due to the use of different materials and methods. Researchers are now studying Roman techniques to improve contemporary building materials.

3. The Astrolabe

What It Is

The astrolabe is a sophisticated ancient astronomical instrument that was historically used to solve various problems related to timekeeping, the position of celestial bodies, and navigation. Developed by Greek astronomers as early as the 2nd century BCE and later refined by Islamic scholars during the Golden Age of Islam, the astrolabe became one of the most important tools in the fields of astronomy, astrology, and navigation. It consists of a flat disk, called the mater, which holds a series of rotating components such as the rete, representing the stars, and other pointers used for measurement.

Astrolabes allowed users to determine the time of day or night by observing the position of the Sun or stars, and they were also used to identify celestial objects, predict their rising and setting times, and even find the direction of Mecca for Islamic prayer. Mariners used a simplified version known as the mariner’s astrolabe for sea navigation by measuring the altitude of the Sun or stars above the horizon, helping to determine latitude.

Throughout antiquity and into the Middle Ages, the astrolabe was not only a practical instrument but also a symbol of scientific and philosophical knowledge. Its use spread across the Mediterranean, the Islamic world, and medieval Europe, influencing scientific thought and aiding in the development of later astronomical tools.

Why It’s Lost

With the advent of more accurate and user-friendly instruments, the astrolabe gradually fell out of common use. One of the major innovations that contributed to its decline was the invention of the sextant in the 18th century. The sextant offered greater precision in measuring the angle between celestial bodies and the horizon, a crucial function for determining latitude at sea. Unlike the astrolabe, which required a high level of expertise and mathematical knowledge to operate effectively, the sextant was more straightforward and reliable under the challenging conditions of maritime navigation.

In the 20th century, technological advancements continued to revolutionize navigation and astronomy. The development of radio-based navigation systems, followed by the introduction of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, rendered older instruments like the astrolabe virtually obsolete. GPS, with its ability to provide real-time, highly accurate location data anywhere on the planet, became the new standard for navigation by the late 20th century.

Additionally, the complexity of the astrolabe itself contributed to its decline. Its use required a deep understanding of astronomy, geometry, and timekeeping, making it accessible primarily to scholars, navigators, and scientists who had undergone specialized training. As newer technologies became widely available and easier to operate, the astrolabe was increasingly viewed as outdated and impractical for modern applications.

Nevertheless, while it is no longer in practical use today, the astrolabe remains a fascinating artifact of scientific history. It continues to be studied and admired for its intricate design, mathematical ingenuity, and historical significance as a symbol of early scientific achievement.

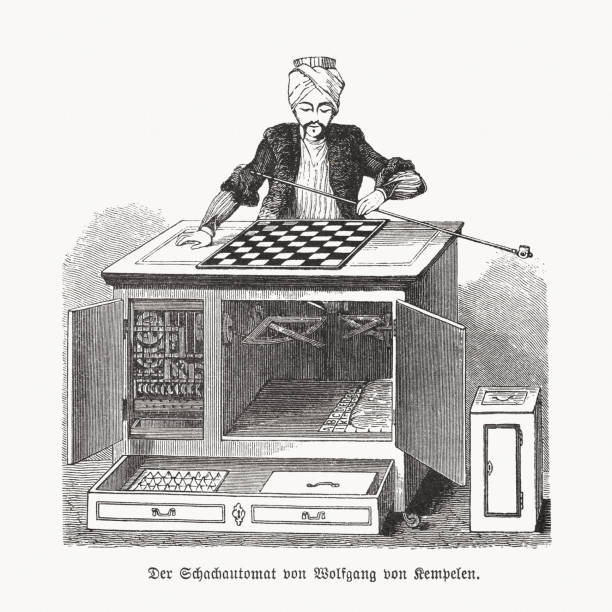

4. The Mechanical Turk

What It Is

The Mechanical Turk was a famous 18th-century automaton that gained widespread attention for its apparent ability to play chess against human opponents. Created in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen, an inventor and civil servant at the court of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, the machine was presented as a marvel of engineering and artificial intelligence, centuries ahead of its time. Housed in a large wooden cabinet with a life-sized figure dressed in Ottoman robes seated at a chessboard, the Mechanical Turk appeared to think and move autonomously, astonishing audiences across Europe and later in America.

The automaton toured extensively, defeating numerous challengers, including prominent figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. It was especially captivating because it seemed to combine human intellect with machine precision—an idea that fascinated Enlightenment-era thinkers. Audiences were shown elaborate demonstrations of the machine’s inner workings before each game to support the illusion that it operated mechanically, using a system of gears, levers, and clockwork mechanisms.

However, the Mechanical Turk was ultimately a cleverly crafted hoax. Unbeknownst to the public, the machine concealed a hidden compartment within the cabinet that allowed a human chess master to sit inside and manipulate the Turk’s movements. Through a system of levers and magnets, the operator could view the board and control the arm of the mannequin, making it appear as though the machine was playing on its own. Over the years, several skilled chess players took turns operating the Turk from within, making the machine seem nearly unbeatable at times.

The secret of the Mechanical Turk was eventually exposed in the 1820s, and the automaton was finally destroyed in a fire in 1854. Despite being a deception, the Mechanical Turk remains an iconic symbol in the history of automation and artificial intelligence. It inspired both skepticism and curiosity about the potential of machines to replicate human thought and continues to be referenced in discussions of AI, robotics, and the ethics of technological illusion..

Why It’s Lost

Once the secret was revealed, the Mechanical Turk lost its allure. The rise of actual automated chess engines and computer algorithms made the concept obsolete, demonstrating that true artificial intelligence was far more complex than a mere mechanical contraption.

5. The Jacquard Loom

What It Is

Invented by French textile manufacturer Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1804, the Jacquard loom represented a groundbreaking advancement in the automation of textile production and is widely recognized as a pivotal development in the history of computing and industrial machinery. The loom was the first to successfully incorporate a form of programmable control through the use of punched cards, which enabled the automatic weaving of intricate and highly detailed patterns into fabric—something that previously required skilled artisans working manually on simpler looms.

The punched cards acted as a set of instructions, encoding the specific pattern to be woven by controlling which threads were raised or lowered at any given time. Each card corresponded to one row of the textile design, and by feeding a sequence of these cards into the loom, complex patterns such as brocades, damasks, and tapestries could be replicated with consistent precision. This innovation not only dramatically increased the efficiency and speed of textile production but also allowed for designs that would have been extraordinarily labor-intensive to produce by hand.

Beyond its impact on the textile industry, the Jacquard loom had profound implications for the future of programmable machines. The concept of using punched cards to control a mechanical process directly influenced later technological developments, particularly in computing. Charles Babbage, often considered the “father of the computer,” cited the Jacquard loom as a key inspiration for his design of the Analytical Engine—a mechanical general-purpose computer conceived in the 1830s. Similarly, punched card systems remained in use well into the 20th century for programming early digital computers and for data storage and processing in businesses and government institutions.

The Jacquard loom was also a symbol of the early Industrial Revolution. It contributed to both the acceleration of mass production and the reshaping of labor practices, particularly in the textile trade. While it offered increased productivity and lower costs, it also sparked resistance among skilled weavers who feared job loss due to mechanization—a conflict echoed in the broader Luddite movement of the time.

Today, the Jacquard loom is not only remembered as a marvel of mechanical engineering but also as a precursor to modern computing, embodying the earliest ideas of machine-readable instruction and programmable automation.

Why It’s Lost

While the Jacquard loom itself is not entirely lost, its original form has been replaced by modern computerized looms. The principles behind it laid the groundwork for modern computing, but the technology itself has evolved significantly.

6. The Dodo Bird’s Extinction

What It Is

While not a form of technology in the traditional, man-made sense, the extinction of the dodo bird is often regarded as a powerful and symbolic example of the irreversible loss of natural “technologies” within ecosystems—unique adaptations and ecological roles that, once gone, cannot be recreated. The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Having evolved in isolation, the dodo had no natural predators and, as a result, lost the instinct to flee and the ability to fly. It grew to a relatively large size and fed mainly on fruits, seeds, and roots found in the island’s forests.

When Dutch sailors arrived on Mauritius in the late 16th century, they encountered the dodo for the first time. Unfortunately, within less than a century of human contact, the species was driven to extinction. This rapid demise, occurring by the late 1600s, was primarily due to overhunting by humans and the introduction of invasive species such as rats, pigs, and monkeys, which preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food resources. Because the bird had no experience with predators, it was especially vulnerable, and its population collapsed within a few decades.

The extinction of the dodo is more than a historical curiosity—it serves as a sobering reminder of the fragile interconnectedness of ecosystems and the unintended consequences of human activity. The dodo played a unique ecological role, possibly including aiding the germination of certain native plant species through seed dispersal. Its disappearance may have triggered subtle but lasting changes in the Mauritian ecosystem, many of which remain poorly understood.

In this sense, the dodo represents a kind of “lost technology” of nature—an evolutionary innovation shaped by millions of years of natural selection, perfectly adapted to a specific environment, and yet entirely unprepared for the sudden pressures introduced by human colonization. Once lost, such ecological roles and evolutionary pathways cannot be easily replaced or replicated.

Today, the dodo has become an enduring cultural symbol of extinction, vulnerability, and the cost of environmental neglect. Its story continues to influence conservation efforts, serving as a cautionary tale that underscores the importance of preserving biodiversity—not just for the sake of individual species, but for the health and sustainability of entire ecosystems.

Why It’s Lost

The dodo’s extinction highlights the impact of human technology on natural ecosystems. As humans developed new tools and methods for hunting and agriculture, species like the dodo could not survive the rapid changes to their environment.

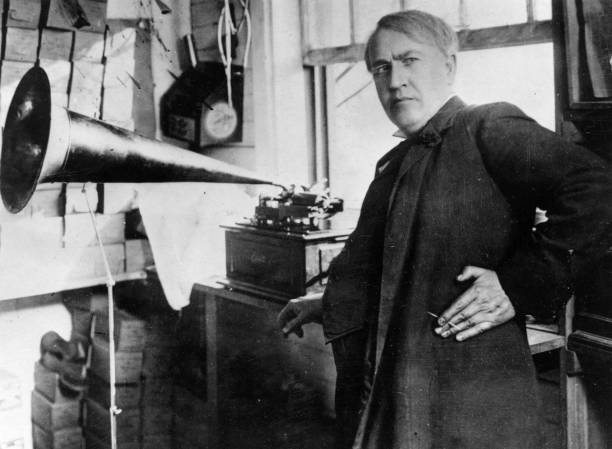

7. The Phonograph Cylinder

What It Is

he phonograph cylinder was one of the earliest practical mediums for recording and reproducing sound, marking a pivotal moment in the history of audio technology. Invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, the device revolutionized the way sound could be captured, stored, and played back—an innovation that laid the groundwork for the modern recording industry. Edison’s original invention involved a tinfoil-covered cylinder that rotated while a stylus etched grooves into its surface in response to sound vibrations. When the stylus retraced those grooves, the vibrations were amplified, reproducing the original sound.

Over time, the design was refined, and wax cylinders replaced tinfoil, offering improved durability, fidelity, and the ability to be mass-produced. These wax cylinders became the primary format for audio recordings from the 1880s through the early 20th century, used for everything from music and storytelling to educational lectures and office dictation. The standard cylinder was capable of playing about two to four minutes of audio, depending on the format and groove density.

The phonograph cylinder’s ability to capture real-time sound opened up new possibilities for both entertainment and archival purposes. It enabled people, for the first time, to hear the voices of individuals long after they were gone, to listen to distant performances without attending in person, and to preserve linguistic, cultural, and musical traditions. These early recordings offer invaluable historical insight and are now considered precious artifacts in the fields of musicology and cultural history.

Although highly innovative for its time, the phonograph cylinder eventually faced competition from flat disc records, which were easier to manufacture, store, and ship. Introduced by Emile Berliner in the late 1880s, disc records—particularly those made from shellac and later vinyl—began to dominate the market by the 1910s. Their longer playtime, better sound quality, and simpler duplication process contributed to the decline of the cylinder format.

Nevertheless, the phonograph cylinder remains an iconic piece of technological history. It symbolizes the dawn of recorded sound and the beginning of a new era in human communication and entertainment. Many modern concepts in audio engineering and playback technology trace their lineage back to the principles first demonstrated by Edison’s invention. Today, preserved phonograph cylinders continue to be studied and digitized by archivists and historians, offering a rare auditory glimpse into the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Why It’s Lost

With the advent of flat disc records and later digital audio formats, phonograph cylinders gradually became obsolete. Although revolutionary in their time, cylinders were fragile, bulky, and offered limited recording durations—typically just two to four minutes of audio. In contrast, flat discs were easier to manufacture, store, and duplicate, and they provided longer playtimes with better sound quality. By the early 20th century, discs had largely taken over the commercial market. As technology advanced further into magnetic tape, compact cassettes, CDs, and eventually digital audio files, the phonograph cylinder faded into history. Its limitations, including physical wear and playback difficulty, rendered it impractical for mass use. However, despite its decline, the phonograph cylinder remains a significant milestone in the evolution of audio recording. It marked the beginning of sound as a preservable, repeatable medium, forever changing the way humans capture and experience audio.

Conclusion

The exploration of lost technologies not only highlights the ingenuity of past civilizations but also serves as a reminder of the impermanence of human innovation. As we continue to advance technologically, it’s essential to reflect on the lessons learned from these lost technologies. Understanding their history can provide insights into our current practices and inspire future innovations that are sustainable and resilient.

As we look to the future, let us not forget the past and the remarkable inventions that shaped our world, even if they are no longer in use.

Source Of Images Freepik.com / Gettyimages.com